This submit discusses the distributional penalties of an aggressive coverage response to inflation utilizing a Heterogeneous Agent New Keynesian (HANK) mannequin. We discover that, when going through demand shocks, stabilizing inflation and actual exercise go hand in hand, with very giant advantages for households on the backside of the wealth distribution. The converse is true nonetheless when going through provide shocks: stabilizing inflation makes actual outcomes extra risky, particularly for poorer households. We conclude that distributional concerns make it way more necessary for coverage to consider the tradeoffs between stabilizing inflation and financial exercise. It’s because the optimum coverage response relies upon very strongly on whether or not these tradeoffs are current (that’s, when the financial system is going through provide shocks) or absent (when the financial system is going through demand shocks).

Demand Shocks

On this submit, we wish to perceive how the volatility of combination and distributional variables (that’s, for example, consumption of the poorest 10 p.c of the inhabitants) adjustments relying on the response perform of the financial authorities. Provided that the U.S. financial system has been experiencing an inflationary episode, we focus particularly on the Fed’s response to inflation and ask how volatility adjustments because the financial authorities reply extra aggressively to inflation. We examine the consequences on volatility as a result of greater volatility means greater financial uncertainty for households, which usually interprets into decrease welfare (though this isn’t essentially at all times the case, as mentioned later).

For causes that may quickly be obvious, it’s useful to establish the completely different sources of volatility in answering this query. Specifically, it’s useful to differentiate so-called demand disturbances—that’s, shocks that push output and inflation in the identical path—from provide disturbances, which push them in the other way and create a tradeoff for the central financial institution. Examples of the previous are shocks arising from the monetary sector: within the aftermath of the nice monetary disaster for example the financial system was depressed and inflation was for an extended interval beneath the Fed’s goal. Examples of the latter are cost-push shocks corresponding to these studied in our companion submit.

We first take a look at so-called demand shocks. The mannequin we use (Lee, 2024) options a lot of these shocks, together with a shock to monetary establishments’ funding preferences (threat premium shocks), a shock to households’ low cost issue (low cost issue shocks), and a shock to transfers from the federal government to people (switch shocks), corresponding to these witnessed within the aftermath of the pandemic.

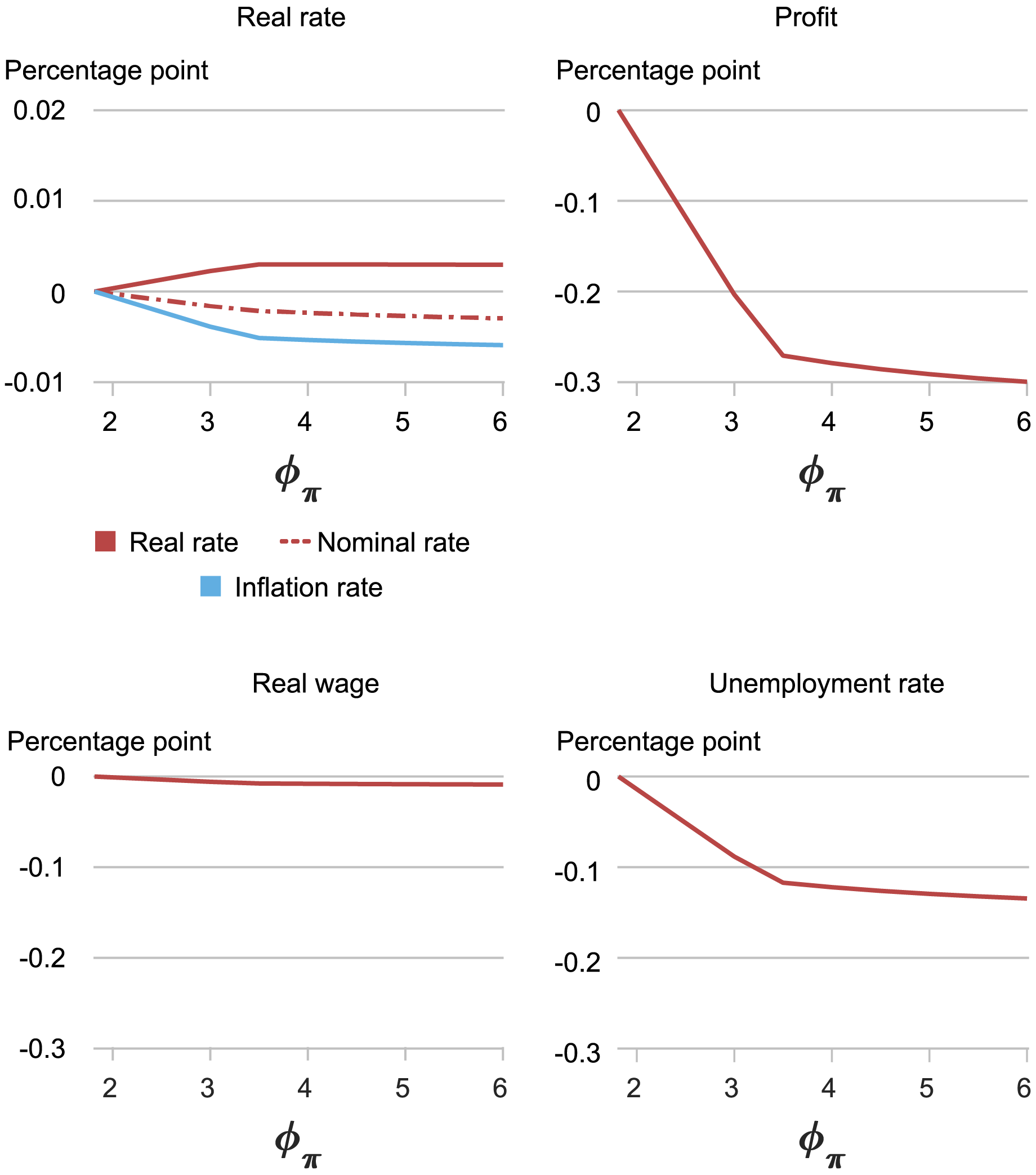

The chart beneath exhibits how the usual deviations of actual and nominal charges, inflation, actual wages, income, and unemployment change as we enhance the coefficient on inflation in our Taylor-like interest-feedback rule beginning at its estimated baseline worth of 1.8. Particularly, the chart depicts share level adjustments in the usual deviation of every variable relative to the baseline. On this train, we assume that the financial system is topic solely to demand shocks. The chart exhibits {that a} extra aggressive response to inflation reduces the volatility not solely of inflation, which is clearly to be anticipated, but additionally of all combination variables besides actual charges. This result’s akin to the so-called “divine coincidence” within the textbook New Keynesian mannequin (although this coincidence doesn’t maintain precisely in HANK fashions): taming inflation is tantamount to taming the true results of the shocks driving inflation. In different phrases, nominal and actual stabilization go hand in hand when the financial system is confronted with demand shocks.

Volatility of Mixture Variables as Coverage Responds Extra Aggressively to Demand Shocks

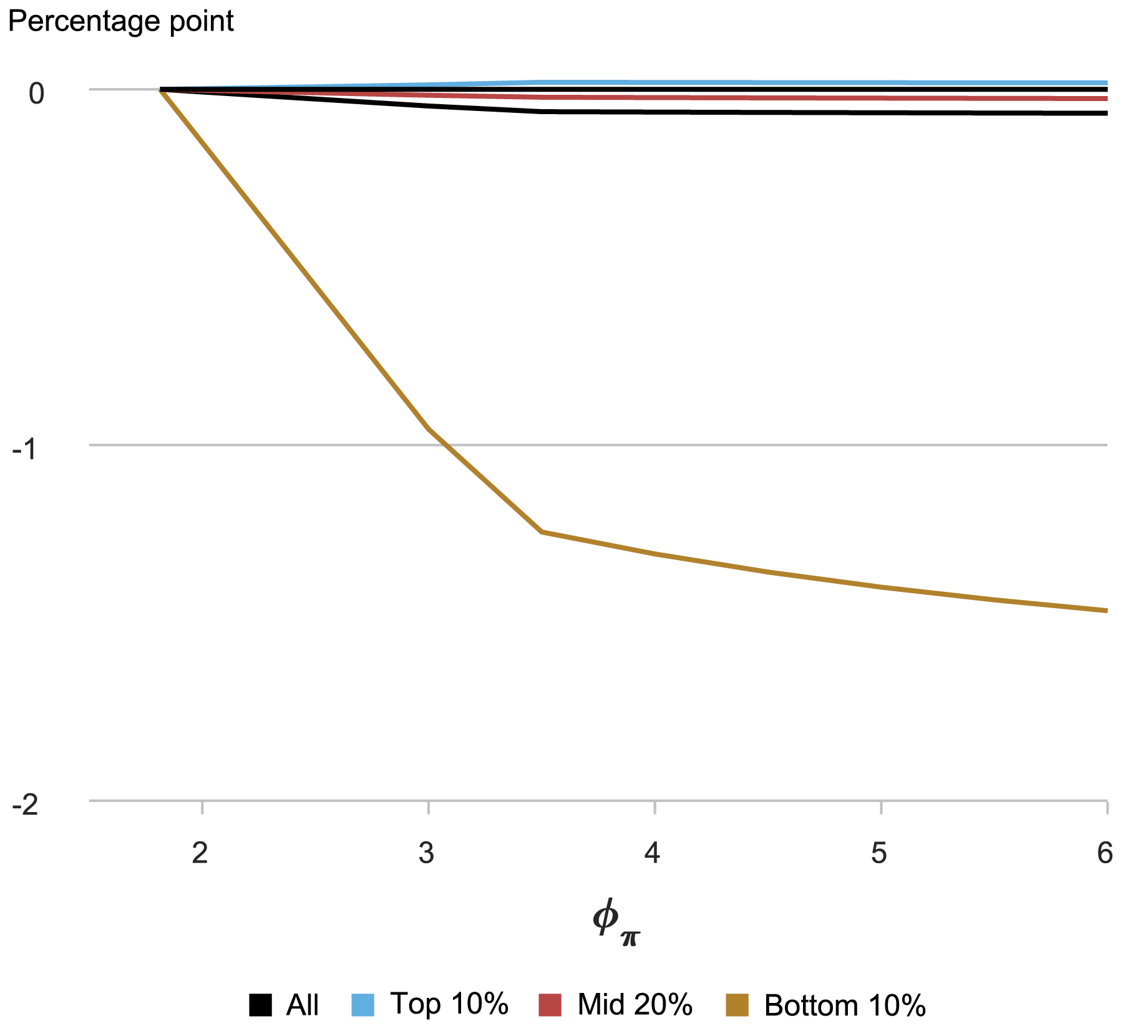

The subsequent chart appears on the distributional implications of adjusting the response to inflation. It exhibits the volatility of consumption for households in several elements of the wealth distribution (particularly, we report the typical change in normal deviation for households within the high and backside 10 p.c of the wealth distribution, the center 20 p.c, and all households).

Volatility of Consumption by Wealth as Coverage Responds Extra Aggressively to Demand Shocks

The chart exhibits that consumption volatility usually declines when the response to inflation is extra aggressive. Once more, the divine coincidence gives instinct for this end result: responding to inflation is tantamount to offsetting the consequences of the shock on financial exercise. Since these are the sources of consumption volatility, offsetting the shock results in decrease volatility. The chart additionally exhibits that the discount in volatility related to a stronger response to inflation is especially hanging for households on the backside of the wealth distribution. That is the case as a result of poor households are extra weak to shocks, as they haven’t any wealth that permits them to easy out the implications of shocks over time (actually, a lot of them are in debt). Wealthier households can use their financial savings buffer to take care of their dwelling requirements even within the face of financial adversities. Households who’ve reached their debt restrict, or are near it, can’t and are, fairly actually, hand-to-mouth. The truth is, even households with some wealth may be successfully hand-to-mouth to the extent that their wealth is illiquid (for instance, housing or pension plans), as a result of making an attempt to make use of this wealth to buffer shocks is expensive.

Provide Shocks

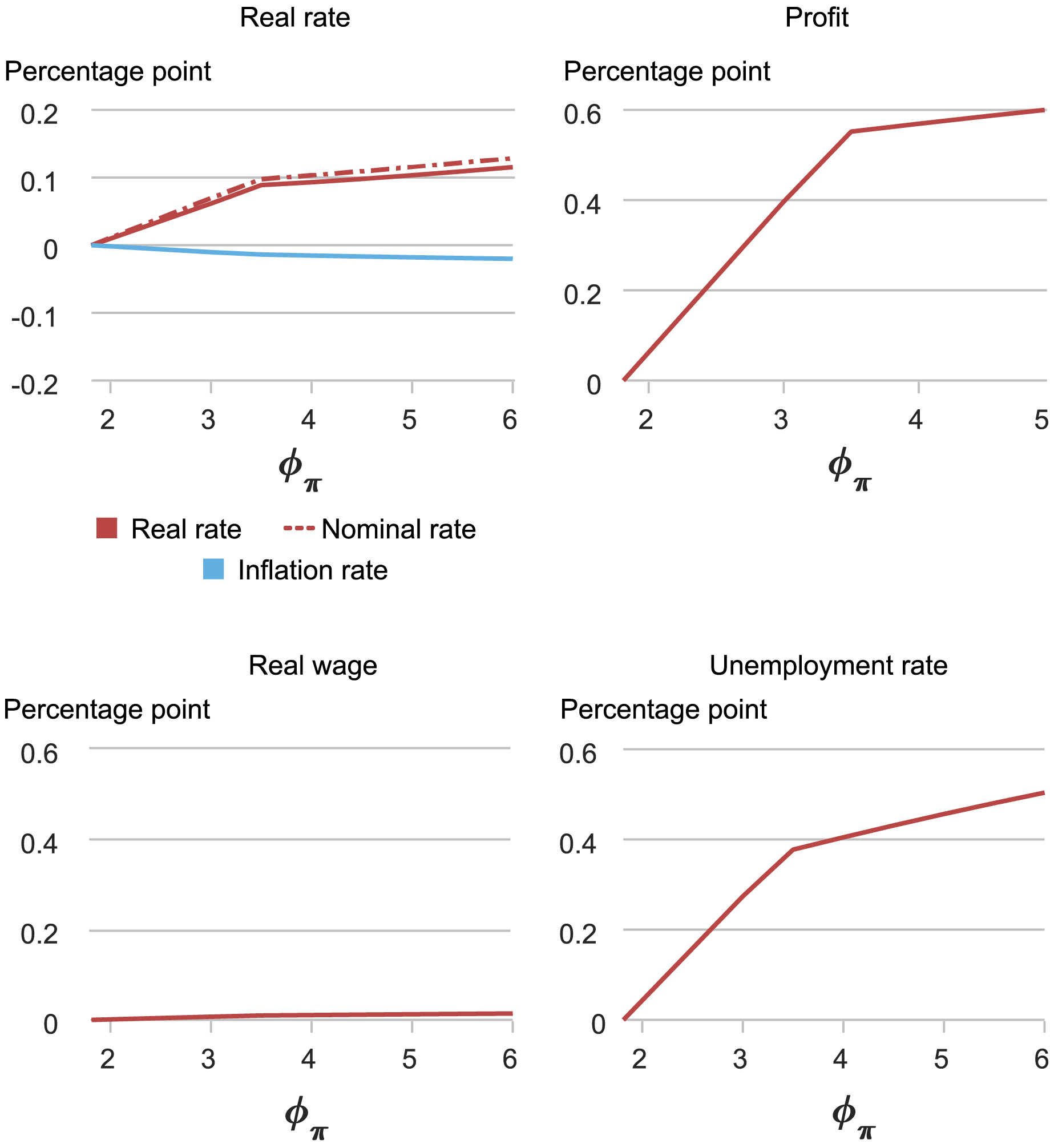

The subsequent two charts present how volatility adjustments for each combination and distributional variables when solely provide shocks, like these thought-about in our companion submit, are current. Clearly, the image could be very completely different. Inflation volatility nonetheless declines because the financial authority responds extra aggressively to inflation, however the divine coincidence now not applies: each combination and distributional variables turn into extra risky as coverage responds extra aggressively to inflation. It’s because provide shocks push actual exercise and inflation in reverse instructions: policymakers can solely stabilize inflation at the price of forcing output and employment farther away from regular state. For example, an antagonistic cost-push shock causes greater inflation and decrease output. The upper inflation can solely be fought by elevating rates of interest and pushing output additional down.

Volatility of Mixture Variables as Coverage Responds Extra Aggressively to Provide Shocks

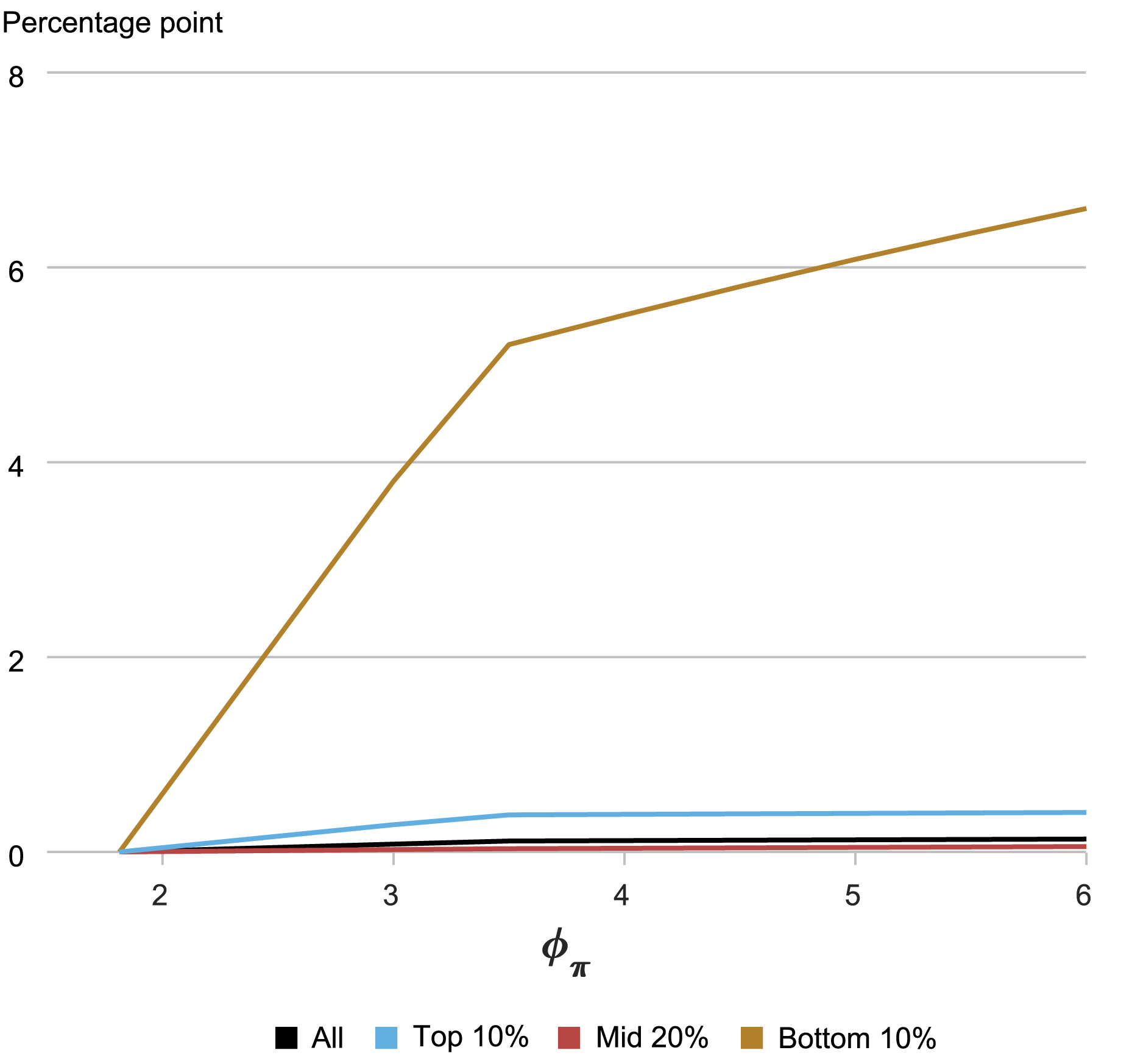

In sum, provide shocks generate a tradeoff for the central financial institution between stabilizing inflation and actual exercise, so {that a} stronger response to inflation leads to greater instability of the true financial system. This instability is especially dangerous for households within the backside 10 p.c of the wealth distribution, as proven within the chart beneath. Within the HANK mannequin with sticky nominal wages these households are significantly damage by inflation volatility as a result of this interprets into fluctuations of their actual wages. If these households are hand-to-mouth, fluctuations in the true wage translate one-to-one into consumption volatility. Regardless of this, the extra volatility in actual exercise generated by a extra aggressive response to inflation hurts poor households much more based on the mannequin, as we have now seen in our companion submit.

Volatility of Consumption by Wealth as Coverage Responds Extra Aggressively to Provide Shocks

Implications for Coverage

Deriving the coverage implications of those outcomes is not any trivial job for a lot of causes. First, we have no idea what disturbances the longer term will deliver. After a few years wherein demand-type shocks just like the monetary disaster gave the impression to be dominant, the world simply skilled an inflationary episode wherein cost-push shocks arguably performed an necessary function. Second, greater/decrease volatility doesn’t at all times translate into decrease/greater welfare. For instance, it might not be optimum to totally stabilize consumption in response to productiveness shocks, as these shocks result in fluctuations within the environment friendly ranges of output that must be accommodated. Straight calculating the impact of different insurance policies on family welfare, nonetheless, would require approximating our mannequin as much as second order, which is technically difficult in HANK fashions (Bhandari et al. 2023 describe one strategy to carry out this approximation; Acharya et al. 2023 examine optimum coverage in a tractable HANK mannequin which could be solved as much as second order in closed type.).

That being stated, our outcomes are broadly consistent with a few of the rising literature on optimum coverage in HANK fashions. It’s well-known that in easy New Keynesian consultant agent fashions Taylor-type suggestions guidelines are usually not optimum. In these fashions the optimum coverage is finest described as a type of ”versatile price-level concentrating on,” wherein coverage places some weight on stabilizing each the worth stage and the output hole (see Svensson and Woodford, 2004). Acharya et al. discover {that a} comparable coverage could be optimum in HANK economies, offered that it places some weight on stabilizing the stage of output, not simply the output hole, and places much less weight on stabilizing costs than can be optimum in a consultant agent New Keynesian mannequin. If a disturbance would are inclined to push inflation and the output hole on the identical facet of the twin mandate—for instance, a detrimental demand shock which reduces each inflation and output—optimum coverage requires aggressively adjusting rates of interest to quash the consequences of the shock and absolutely stabilize each variables. But when the disturbances trigger inflation and the output hole to be on the alternative facet of the twin mandate, as is the case with cost-push shocks, optimum coverage requires a much less aggressive response, given the tradeoff between stabilizing inflation and financial exercise. Taking into consideration the distributional implications of financial coverage—as we have now finished in these posts—means that accounting for the tradeoff between inflation and financial exercise is much more necessary than when these distributional penalties are ignored.

Marco Del Negro is an financial analysis advisor in Macroeconomic and Financial Research within the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York’s Analysis and Statistics Group.

Keshav Dogra is a senior economist and financial analysis advisor in Macroeconomic and Financial Research within the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York’s Analysis and Statistics Group.

Pranay Gundam is a analysis analyst within the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York’s Analysis and Statistics Group.

Donggyu Lee is a analysis economist in Macroeconomic and Financial Research within the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York’s Analysis and Statistics Group.

Brian Pacula is a analysis analyst within the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York’s Analysis and Statistics Group.

cite this submit:

Marco Del Negro, Keshav Dogra, Pranay Gundam, Donggyu Lee, and Brian Pacula, “On the Distributional Penalties of Responding Aggressively to Inflation,” Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York Liberty Avenue Economics, July 3, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/07/on-the-distributional-consequences-of-responding-aggressively-to-inflation/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed on this submit are these of the writer(s) and don’t essentially mirror the place of the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the accountability of the writer(s).